11.9. Large-Scale Pretraining with Transformers¶ Open the notebook in SageMaker Studio Lab

So far in our image classification and machine translation experiments, models have been trained on datasets with input–output examples from scratch to perform specific tasks. For example, a Transformer was trained with English–French pairs (Section 11.7) so that this model can translate input English text into French. As a result, each model becomes a specific expert that is sensitive to even a slight shift in data distribution (Section 4.7). For better generalized models, or even more competent generalists that can perform multiple tasks with or without adaptation, pretraining models on large data has been increasingly common.

Given larger data for pretraining, the Transformer architecture performs better with an increased model size and training compute, demonstrating superior scaling behavior. Specifically, performance of Transformer-based language models scales as a power law with the amount of model parameters, training tokens, and training compute (Kaplan et al., 2020). The scalability of Transformers is also evidenced by the significantly boosted performance from larger vision Transformers trained on larger data (discussed in Section 11.8). More recent success stories include Gato, a generalist model that can play Atari, caption images, chat, and act as a robot (Reed et al., 2022). Gato is a single Transformer that scales well when pretrained on diverse modalities, including text, images, joint torques, and button presses. Notably, all such multimodal data is serialized into a flat sequence of tokens, which can be processed akin to text tokens (Section 11.7) or image patches (Section 11.8) by Transformers.

Prior to the compelling success of pretraining Transformers for multimodal data, Transformers were extensively pretrained with a wealth of text. Originally proposed for machine translation, the Transformer architecture in Fig. 11.7.1 consists of an encoder for representing input sequences and a decoder for generating target sequences. Primarily, Transformers can be used in three different modes: encoder-only, encoder–decoder, and decoder-only. To conclude this chapter, we will review these three modes and explain the scalability in pretraining Transformers.

11.9.1. Encoder-Only¶

When only the Transformer encoder is used, a sequence of input tokens is converted into the same number of representations that can be further projected into output (e.g., classification). A Transformer encoder consists of self-attention layers, where all input tokens attend to each other. For example, vision Transformers depicted in Fig. 11.8.1 are encoder-only, converting a sequence of input image patches into the representation of a special “<cls>” token. Since this representation depends on all input tokens, it is further projected into classification labels. This design was inspired by an earlier encoder-only Transformer pretrained on text: BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) (Devlin et al., 2018).

11.9.1.1. Pretraining BERT¶

Fig. 11.9.1 Left: Pretraining BERT with masked language modeling. Prediction of the masked “love” token depends on all input tokens before and after “love”. Right: Attention pattern in the Transformer encoder. Each token along the vertical axis attends to all input tokens along the horizontal axis.¶

BERT is pretrained on text sequences using masked language modeling: input text with randomly masked tokens is fed into a Transformer encoder to predict the masked tokens. As illustrated in Fig. 11.9.1, an original text sequence “I”, “love”, “this”, “red”, “car” is prepended with the “<cls>” token, and the “<mask>” token randomly replaces “love”; then the cross-entropy loss between the masked token “love” and its prediction is to be minimized during pretraining. Note that there is no constraint in the attention pattern of Transformer encoders (right of Fig. 11.9.1) so all tokens can attend to each other. Thus, prediction of “love” depends on input tokens before and after it in the sequence. This is why BERT is a “bidirectional encoder”. Without need for manual labeling, large-scale text data from books and Wikipedia can be used for pretraining BERT.

11.9.1.2. Fine-Tuning BERT¶

The pretrained BERT can be fine-tuned to downstream encoding tasks involving single text or text pairs. During fine-tuning, additional layers can be added to BERT with randomized parameters: these parameters and those pretrained BERT parameters will be updated to fit training data of downstream tasks.

Fig. 11.9.2 Fine-tuning BERT for sentiment analysis.¶

Fig. 11.9.2 illustrates fine-tuning of BERT for sentiment analysis. The Transformer encoder is a pretrained BERT, which takes a text sequence as input and feeds the “<cls>” representation (global representation of the input) into an additional fully connected layer to predict the sentiment. During fine-tuning, the cross-entropy loss between the prediction and the label on sentiment analysis data is minimized via gradient-based algorithms, where the additional layer is trained from scratch while pretrained parameters of BERT are updated. BERT does more than sentiment analysis. The general language representations learned by the 350-million-parameter BERT from 250 billion training tokens advanced the state of the art for natural language tasks such as single text classification, text pair classification or regression, text tagging, and question answering.

You may note that these downstream tasks include text pair understanding. BERT pretraining has another loss for predicting whether one sentence immediately follows the other. However, this loss was later found to be less useful when pretraining RoBERTa, a BERT variant of the same size, on 2000 billion tokens (Liu et al., 2019). Other derivatives of BERT improved model architectures or pretraining objectives, such as ALBERT (enforcing parameter sharing) (Lan et al., 2019), SpanBERT (representing and predicting spans of text) (Joshi et al., 2020), DistilBERT (lightweight via knowledge distillation) (Sanh et al., 2019), and ELECTRA (replaced token detection) (Clark et al., 2020). Moreover, BERT inspired Transformer pretraining in computer vision, such as with vision Transformers (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021), Swin Transformers (Liu et al., 2021), and MAE (masked autoencoders) (He et al., 2022).

11.9.2. Encoder–Decoder¶

Since a Transformer encoder converts a sequence of input tokens into the same number of output representations, the encoder-only mode cannot generate a sequence of arbitrary length as in machine translation. As originally proposed for machine translation, the Transformer architecture can be outfitted with a decoder that autoregressively predicts the target sequence of arbitrary length, token by token, conditional on both encoder output and decoder output: (i) for conditioning on encoder output, encoder–decoder cross-attention (multi-head attention of decoder in Fig. 11.7.1) allows target tokens to attend to all input tokens; (ii) conditioning on decoder output is achieved by a so-called causal attention (this name is common in the literature but is misleading as it has little connection to the proper study of causality) pattern (masked multi-head attention of decoder in Fig. 11.7.1), where any target token can only attend to past and present tokens in the target sequence.

To pretrain encoder–decoder Transformers beyond human-labeled machine translation data, BART (Lewis et al., 2019) and T5 (Raffel et al., 2020) are two concurrently proposed encoder–decoder Transformers pretrained on large-scale text corpora. Both attempt to reconstruct original text in their pretraining objectives, while the former emphasizes noising input (e.g., masking, deletion, permutation, and rotation) and the latter highlights multitask unification with comprehensive ablation studies.

11.9.2.1. Pretraining T5¶

As an example of the pretrained Transformer encoder–decoder, T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) unifies many tasks as the same text-to-text problem: for any task, the input of the encoder is a task description (e.g., “Summarize”, “:”) followed by task input (e.g., a sequence of tokens from an article), and the decoder predicts the task output (e.g., a sequence of tokens summarizing the input article). To perform as text-to-text, T5 is trained to generate some target text conditional on input text.

Fig. 11.9.3 Left: Pretraining T5 by predicting consecutive spans. The original sentence is “I”, “love”, “this”, “red”, “car”, where “love” is replaced by a special “<X>” token, and consecutive “red”, “car” are replaced by a special “<Y>” token. The target sequence ends with a special “<Z>” token. Right: Attention pattern in the Transformer encoder–decoder. In the encoder self-attention (lower square), all input tokens attend to each other; In the encoder–decoder cross-attention (upper rectangle), each target token attends to all input tokens; In the decoder self-attention (upper triangle), each target token attends to present and past target tokens only (causal).¶

To obtain input and output from any original text, T5 is pretrained to predict consecutive spans. Specifically, tokens from text are randomly replaced by special tokens where each consecutive span is replaced by the same special token. Consider the example in Fig. 11.9.3, where the original text is “I”, “love”, “this”, “red”, “car”. Tokens “love”, “red”, “car” are randomly replaced by special tokens. Since “red” and “car” are a consecutive span, they are replaced by the same special token. As a result, the input sequence is “I”, “<X>”, “this”, “<Y>”, and the target sequence is “<X>”, “love”, “<Y>”, “red”, “car”, “<Z>”, where “<Z>” is another special token marking the end. As shown in Fig. 11.9.3, the decoder has a causal attention pattern to prevent itself from attending to future tokens during sequence prediction.

In T5, predicting consecutive span is also referred to as reconstructing corrupted text. With this objective, T5 is pretrained with 1000 billion tokens from the C4 (Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus) data, which consists of clean English text from the web (Raffel et al., 2020).

11.9.2.2. Fine-Tuning T5¶

Similar to BERT, T5 needs to be fine-tuned (updating T5 parameters) on task-specific training data to perform this task. Major differences from BERT fine-tuning include: (i) T5 input includes task descriptions; (ii) T5 can generate sequences with arbitrary length with its Transformer decoder; (iii) No additional layers are required.

Fig. 11.9.4 Fine-tuning T5 for text summarization. Both the task description and article tokens are fed into the Transformer encoder for predicting the summary.¶

Fig. 11.9.4 explains fine-tuning T5 using text summarization as an example. In this downstream task, the task description tokens “Summarize”, “:” followed by the article tokens are input to the encoder.

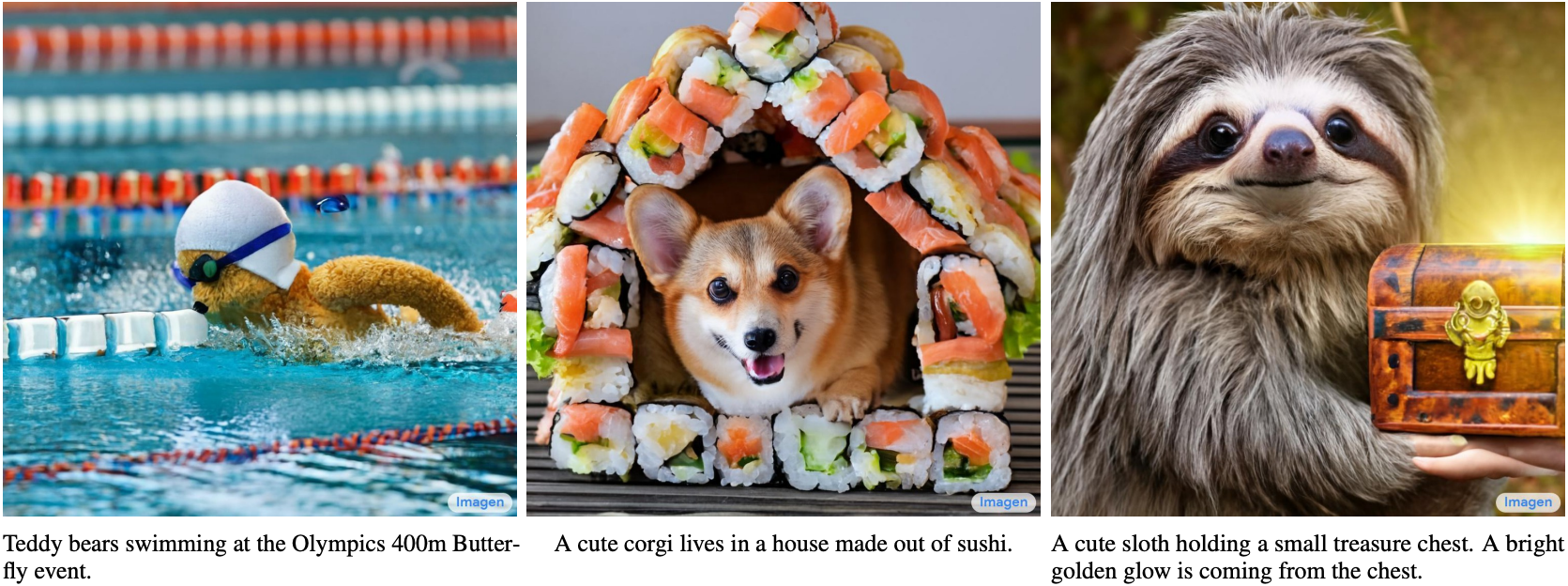

After fine-tuning, the 11-billion-parameter T5 (T5-11B) achieved state-of-the-art results on multiple encoding (e.g., classification) and generation (e.g., summarization) benchmarks. Since released, T5 has been extensively used in later research. For example, switch Transformers are designed based on T5 to activate a subset of the parameters for better computational efficiency (Fedus et al., 2022). In a text-to-image model called Imagen, text is input to a frozen T5 encoder (T5-XXL) with 4.6 billion parameters (Saharia et al., 2022). The photorealistic text-to-image examples in Fig. 11.9.5 suggest that the T5 encoder alone may effectively represent text even without fine-tuning.

11.9.3. Decoder-Only¶

We have reviewed encoder-only and encoder–decoder Transformers. Alternatively, decoder-only Transformers remove the entire encoder and the decoder sublayer with the encoder–decoder cross-attention from the original encoder–decoder architecture depicted in Fig. 11.7.1. Nowadays, decoder-only Transformers have been the de facto architecture in large-scale language modeling (Section 9.3), which leverages the world’s abundant unlabeled text corpora via self-supervised learning.

11.9.3.1. GPT and GPT-2¶

Using language modeling as the training objective, the GPT (generative pre-training) model chooses a Transformer decoder as its backbone (Radford et al., 2018).

Fig. 11.9.6 Left: Pretraining GPT with language modeling. The target sequence is the input sequence shifted by one token. Both “<bos>” and “<eos>” are special tokens marking the beginning and end of sequences, respectively. Right: Attention pattern in the Transformer decoder. Each token along the vertical axis attends to only its past tokens along the horizontal axis (causal).¶

Following the autoregressive language model training as described in Section 9.3.3, Fig. 11.9.6 illustrates GPT pretraining with a Transformer encoder, where the target sequence is the input sequence shifted by one token. Note that the attention pattern in the Transformer decoder enforces that each token can only attend to its past tokens (future tokens cannot be attended to because they have not yet been chosen).

GPT has 100 million parameters and needs to be fine-tuned for individual downstream tasks. A much larger Transformer-decoder language model, GPT-2, was introduced one year later (Radford et al., 2019). Compared with the original Transformer decoder in GPT, pre-normalization (discussed in Section 11.8.3) and improved initialization and weight-scaling were adopted in GPT-2. Pretrained on 40 GB of text, the 1.5-billion-parameter GPT-2 obtained the state-of-the-art results on language modeling benchmarks and promising results on multiple other tasks without updating the parameters or architecture.

11.9.3.2. GPT-3 and Beyond¶

GPT-2 demonstrated potential of using the same language model for multiple tasks without updating the model. This is more computationally efficient than fine-tuning, which requires model updates via gradient computation.

Fig. 11.9.7 Zero-shot, one-shot, few-shot in-context learning with language models (Transformer decoders). No parameter update is needed.¶

Before explaining the more computationally efficient use of language models without parameter update, recall Section 9.5 that a language model can be trained to generate a text sequence conditional on some prefix text sequence. Thus, a pretrained language model may generate the task output as a sequence without parameter update, conditional on an input sequence with the task description, task-specific input–output examples, and a prompt (task input). This learning paradigm is called in-context learning (Brown et al., 2020), which can be further categorized into zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot, when there is no, one, and a few task-specific input–output examples (Fig. 11.9.7).

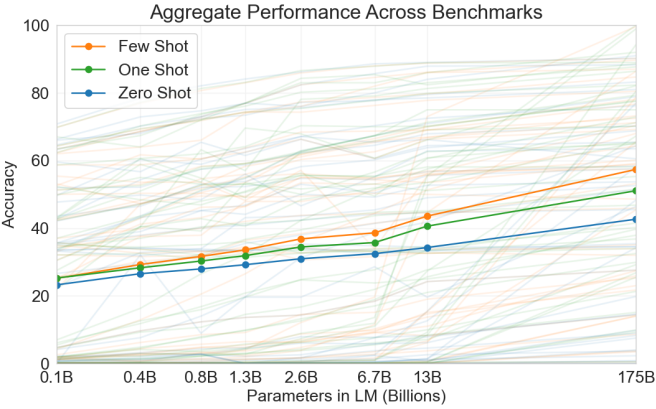

Fig. 11.9.8 Aggregate performance of GPT-3 for all 42 accuracy-denominated benchmarks (caption adapted and figure taken from Brown et al. (2020)).¶

These three settings were tested in GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020), whose largest version uses data and model size about two orders of magnitude larger than those in GPT-2. GPT-3 uses the same Transformer decoder architecture as its direct predecessor GPT-2 except that attention patterns (at the right in Fig. 11.9.6) are sparser at alternating layers. Pretrained with 300 billion tokens, GPT-3 performs better with larger model size, where few-shot performance increases most rapidly (Fig. 11.9.8).

The subsequent GPT-4 model did not fully disclose technical details in its report (OpenAI, 2023). By contrast with its predecessors, GPT-4 is a large-scale, multimodal model that can take both text and images as input and generate text output.

11.9.4. Scalability¶

Fig. 11.9.8 empirically demonstrates scalability of Transformers in the GPT-3 language model. For language modeling, more comprehensive empirical studies on the scalability of Transformers have led researchers to see promise in training larger Transformers with more data and compute (Kaplan et al., 2020).

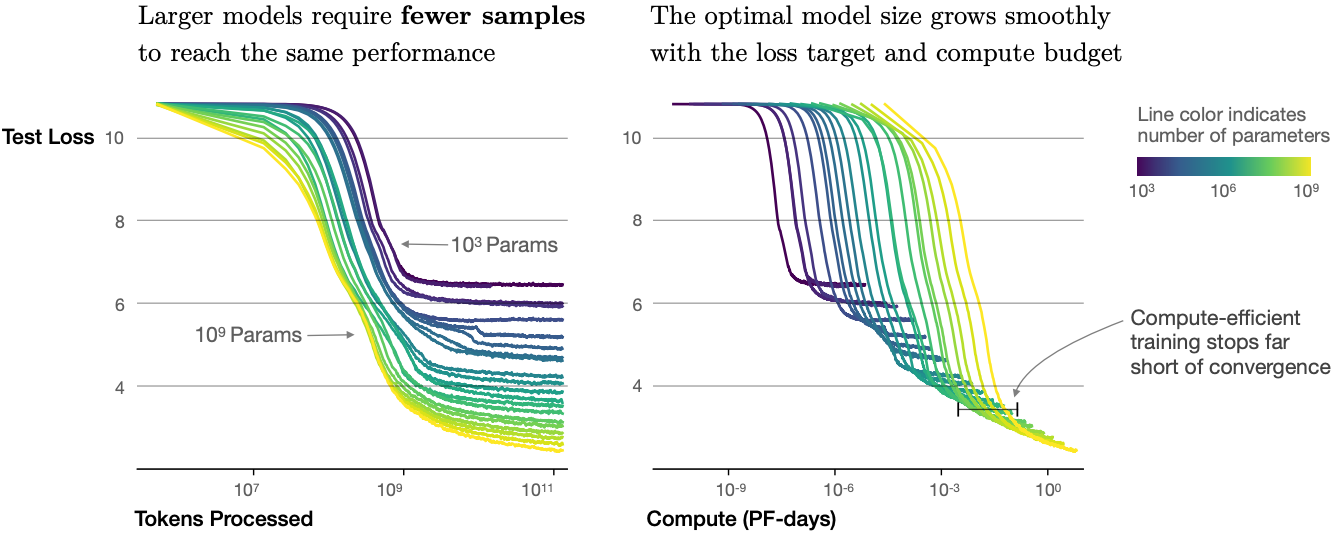

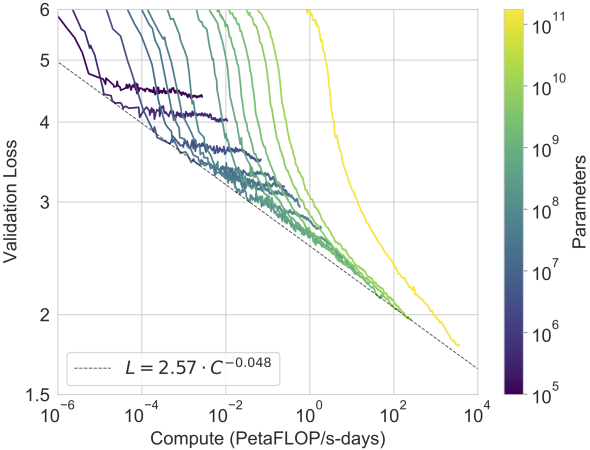

Fig. 11.9.9 Transformer language model performance improves smoothly as we increase the model size, dataset size, and amount of compute used for training. For optimal performance all three factors must be scaled up in tandem. Empirical performance has a power-law relationship with each individual factor when not bottlenecked by the other two (caption adapted and figure taken from Kaplan et al. (2020)).¶

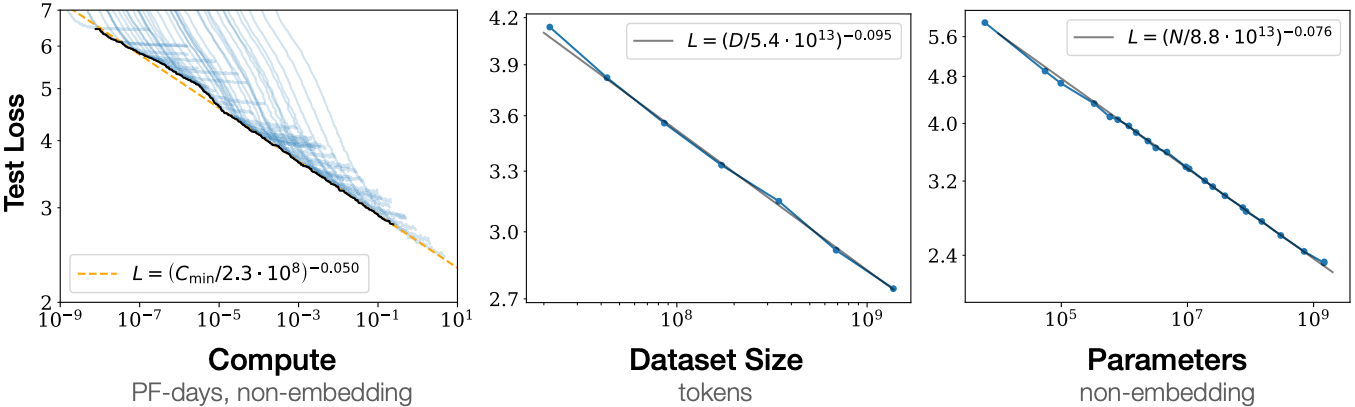

As shown in Fig. 11.9.9, power-law scaling can be observed in the performance with respect to the model size (number of parameters, excluding embedding layers), dataset size (number of training tokens), and amount of training compute (PetaFLOP/s-days, excluding embedding layers). In general, increasing all these three factors in tandem leads to better performance. However, how to increase them in tandem still remains a matter of debate (Hoffmann et al., 2022).

As well as increased performance, large models also enjoy better sample efficiency than small models. Fig. 11.9.10 shows that large models need fewer training samples (tokens processed) to perform at the same level achieved by small models, and performance is scaled smoothly with compute.

Fig. 11.9.11 GPT-3 performance (cross-entropy validation loss) follows a power-law trend with the amount of compute used for training. The power-law behavior observed in Kaplan et al. (2020) continues for an additional two orders of magnitude with only small deviations from the predicted curve. Embedding parameters are excluded from compute and parameter counts (caption adapted and figure taken from Brown et al. (2020)).¶

The empirical scaling behaviors in Kaplan et al. (2020) have been tested in subsequent large Transformer models. For example, GPT-3 supported this hypothesis with two more orders of magnitude in Fig. 11.9.11.

11.9.5. Large Language Models¶

The scalability of Transformers in the GPT series has inspired subsequent large language models. The GPT-2 Transformer decoder was used for training the 530-billion-parameter Megatron-Turing NLG (Smith et al., 2022) with 270 billion training tokens. Following the GPT-2 design, the 280-billion-parameter Gopher (Rae et al., 2021) pretrained with 300 billion tokens, performed competitively across diverse tasks. Inheriting the same architecture and using the same compute budget of Gopher, Chinchilla (Hoffmann et al., 2022) is a substantially smaller (70 billion parameters) model that trains for much longer (1.4 trillion training tokens), outperforming Gopher on many tasks and with more emphasis on the number of tokens than on the number of parameters. To continue the scaling line of language modeling, PaLM (Pathway Language Model) (Chowdhery et al., 2022), a 540-billion-parameter Transformer decoder with modified designs pretrained on 780 billion tokens, outperformed average human performance on the BIG-Bench benchmark (Srivastava et al., 2022). Its later version, PaLM 2 (Anil et al., 2023), scaled data and model roughly 1:1 and improved multilingual and reasoning capabilities. Other large language models, such as Minerva (Lewkowycz et al., 2022) that further trains a generalist (PaLM) and Galactica (Taylor et al., 2022) that is not trained on a general corpus, have shown promising quantitative and scientific reasoning capabilities.

Open-sourced releases, such as OPT (Open Pretrained Transformers) (Zhang et al., 2022), BLOOM (Scao et al., 2022), and FALCON (Penedo et al., 2023), democratized research and use of large language models. Focusing on computational efficiency at inference time, the open-sourced Llama 1 (Touvron et al., 2023a) outperformed much larger models by training on more tokens than had been typically used. The updated Llama 2 (Touvron et al., 2023b) further increased the pretraining corpus by 40%, leading to product models that may match the performance of competitive close-sourced models.

Wei et al. (2022) discussed emergent abilities of large language models that are present in larger models, but not in smaller models. However, simply increasing model size does not inherently make models follow human instructions better. Sanh et al. (2021), Wei et al. (2021) have found that fine-tuning large language models on a range of datasets described via instructions can improve zero-shot performance on held-out tasks. Using reinforcement learning from human feedback, Ouyang et al. (2022) fine-tuned GPT-3 to follow a diverse set of instructions. Following the resultant InstructGPT which aligns language models with human intent via fine-tuning (Ouyang et al., 2022), ChatGPT can generate human-like responses (e.g., code debugging and creative writing) based on conversations with humans and can perform many natural language processing tasks zero-shot (Qin et al., 2023). Bai et al. (2022) replaced human inputs (e.g., human-labeled data) with model outputs to partially automate the instruction tuning process, which is also known as reinforcement learning from AI feedback.

Large language models offer an exciting prospect of formulating text input to induce models to perform desired tasks via in-context learning, which is also known as prompting. Notably, chain-of-thought prompting (Wei et al., 2022), an in-context learning method with few-shot “question, intermediate reasoning steps, answer” demonstrations, elicits the complex reasoning capabilities of large language models in order to solve mathematical, commonsense, and symbolic reasoning tasks. Sampling multiple reasoning paths (Wang et al., 2023), diversifying few-shot demonstrations (Zhang et al., 2023), and reducing complex problems to sub-problems (Zhou et al., 2023) can all improve the reasoning accuracy. In fact, with simple prompts like “Let’s think step by step” just before each answer, large language models can even perform zero-shot chain-of-thought reasoning with decent accuracy (Kojima et al., 2022). Even for multimodal inputs consisting of both text and images, language models can perform multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning with higher accuracy than using text input only (Zhang et al., 2023).

11.9.6. Summary and Discussion¶

Transformers have been pretrained as encoder-only (e.g., BERT), encoder–decoder (e.g., T5), and decoder-only (e.g., GPT series). Pretrained models may be adapted to perform different tasks with model update (e.g., fine-tuning) or not (e.g., few-shot). Scalability of Transformers suggests that better performance benefits from larger models, more training data, and more training compute. Since Transformers were first designed and pretrained for text data, this section leans slightly towards natural language processing. Nonetheless, those models discussed above can be often found in more recent models across multiple modalities. For example, (i) Chinchilla (Hoffmann et al., 2022) was further extended to Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022), a visual language model for few-shot learning; (ii) GPT-2 (Radford et al., 2019) and the vision Transformer encode text and images in CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) (Radford et al., 2021), whose image and text embeddings were later adopted in the DALL-E 2 text-to-image system (Ramesh et al., 2022). Although there have been no systematic studies on Transformer scalability in multimodal pretraining yet, an all-Transformer text-to-image model called Parti (Yu et al., 2022) shows potential of scalability across modalities: a larger Parti is more capable of high-fidelity image generation and content-rich text understanding (Fig. 11.9.12).

11.9.7. Exercises¶

Is it possible to fine-tune T5 using a minibatch consisting of different tasks? Why or why not? How about for GPT-2?

Given a powerful language model, what applications can you think of?

Say that you are asked to fine-tune a language model to perform text classification by adding additional layers. Where will you add them? Why?

Consider sequence-to-sequence problems (e.g., machine translation) where the input sequence is always available throughout the target sequence prediction. What could be limitations of modeling with decoder-only Transformers? Why?